МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫЙ СЕЛЬСКОХОЗЯЙСТВЕННЫЙ ЖУРНАЛ № 6 / 2016

7

ÌÑÕÆ — 60 ëåò!

ГЛАВНАЯ ТЕМА НОМЕРА

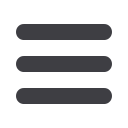

On one hand, the majority of land was cultivat-

ed by small farms only in Latvia, Lithuania, Poland,

Romania and Slovenia. In Poland and Slovenia,

small scale farms dominated agriculture during the

socialist period and they have not been changed

much after 1990 (Csáki and Jámbor, 2013). On the

other hand, large farms ruled land use in the other

five countries. Values of Czech Republic and Slova-

kia (around 90% for large farms) show an extreme

dominance of large scale farming. However, medi-

um-scale farming is missing in most cases. These

land use patterns stayed relatively stable if compar-

ing these results to pre-accession levels. Concern-

ing the impact of farm structures on post-accession

performances, it is evident that in Poland and Slo-

venia small scale agriculture proved to be benefi-

cial, while the dominance of large scale farming

seemed to have detrimental impacts on country

performances except for Estonia.

Differently implemented land and farm con-

solidation policies had also diverse effects on post-

accession country performance. Restrictive pre-

accession land policies and the lack of land and

farm consolidation (e.g. in Hungary) has negatively

influenced the capacity to take advantage of the

enlarged markets by significantly constraining the

flow of capital outside the agricultural sector (Ci-

aian et al. 2010). Conversely, liberal land policies

(e.g. in Baltic countries) helped the agricultural sec-

tor to obtain more resources and utilise the pos-

sibilities created by the accession better. In other

words, those countries with restrictive land poli-

cies, as also suggested by Swinnen and Vranken

(2010), performed worse.

The magnitude of privatisation in the agri-food

sector and the type of foreign ownership also af-

fected post-accession performances. After the col-

lapse of the Soviet markets there was a massive

privatisation of the agri-food sector in the majority

of NMS. Those countries giving ownership of food

processing companies to local farmers (e.g. Czech

Republic, Poland) performed better, while the rapid

rise of foreign ownership together with fast privati-

sation resulted in worse performances in the long

run (e.g. Bulgaria, Hungary, Romania).

The ways in which the countries used EU-fund-

ed pre-accession programmes such as SAPARD,

ISPA and PHARE was also important. Those who fo-

cused on competitiveness enhancement and pro-

duction improvement were better in realising the

benefits after accession. On the contrary, delays

in creating the required institutions as well as the

initial disturbances of implementation resulted in

the loss of some EU funds in a number of countries

(Csáki-Jámbor, 2013).

The diversity of the macro environment also

had an impact (

Figure 4

). Annual average GDP

growth in the NMS was the highest in Latvia for

the first two periods and Poland for the third, while

the lowest in Bulgaria, Hungary and Slovenia in the

three respective periods. Note that it was only Es-

tonia and Poland whose annual GDP growth re-

mained positive in the third period when the ef-

fects of the 2008 economic crisis was the biggest.

Volatility and transparency of agricultural poli-

cies were probably the most important reasons be-

hind different performances. Changing agricultural

policies, usually taking a u-turn after elections, were

very much against the long-termgrowth of the agri-

food sector. Those countries with reliable and trans-

parent policies (e.g. Poland) could reach better re-

sults than those with fire-brigade agri-food policy

making during the past decade (e.g. Hungary). The

consistency of agri-food policy making is also re-

flected in the existence of long-term agriculture and

rural development strategies of which the majority

in the region was in lack (Potori et al. 2013).

The focus of total payments on agriculture also

determined agri-food performances. Before acces-

sion, payments in favour of competitiveness en-

hancement definitely proved to be beneficial. On

one hand, those countries, where agricultural sub-

sidies to farmers remained at a lower level (e.g. Po-

land), have gained much with the accession which

has provided visible incentives for production and

led to an increase of agri-food trade balance. On

the other hand, those countries providing initially

high and uneven price and market support (e.g.

Bulgaria, Romania, Hungary) were considered to

lose with accession as it has brought hardly any

price increase. Agricultural policy aimed to en-

hance competitiveness was a failure and resulted

in a situation where the majority of farmers were

not prepared for the accession (Csáki-Jámbor, 2013,

Popp-Jambor, 2015).

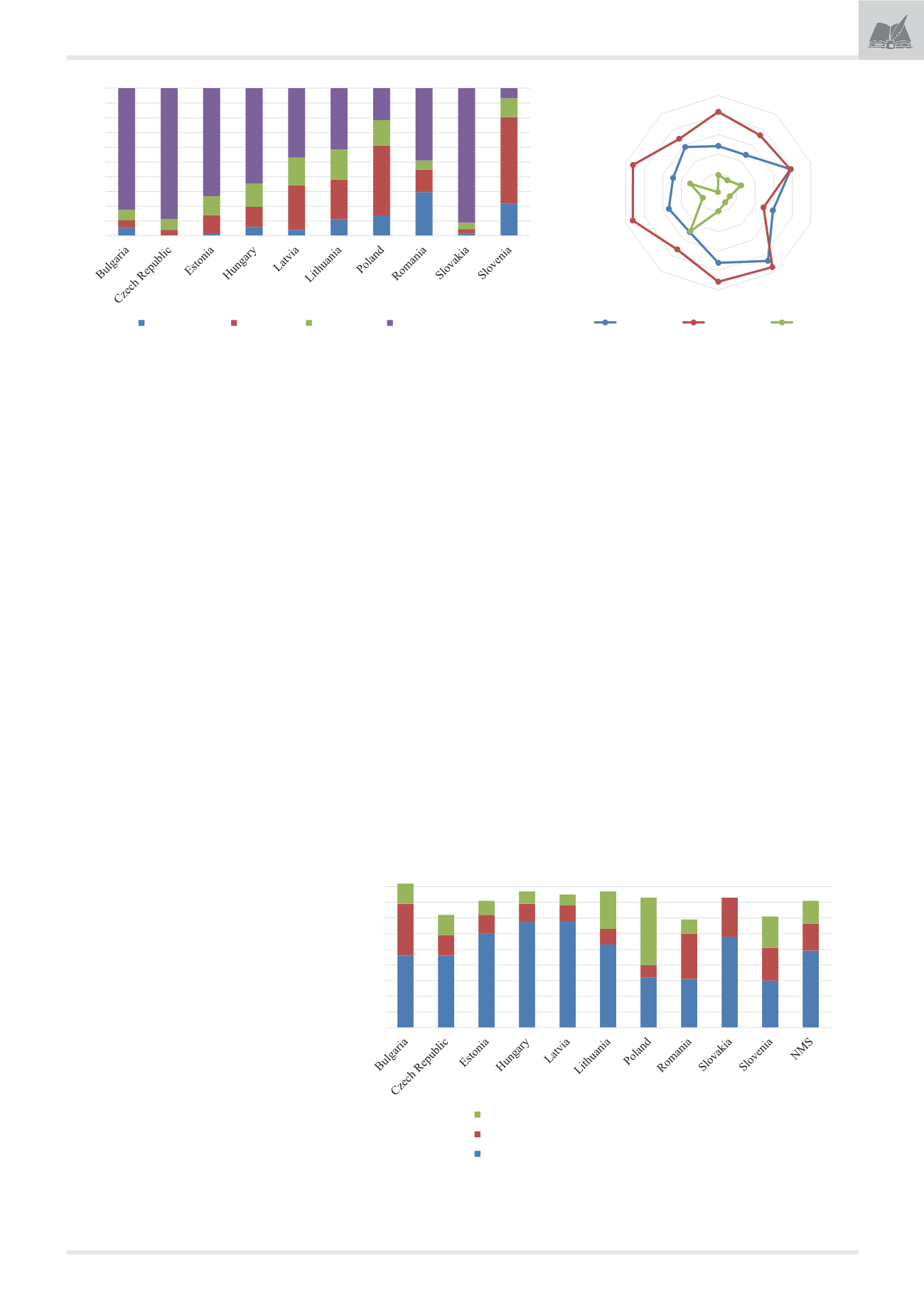

Regarding the focus of total payments on ag-

riculture, a different picture appears after acces-

sion. Interestingly, those countries that spent less

than the regional average on value added generally

performed better (

Figure 5

). On one hand, Bulgar-

ia, Romania and Slovakia spent more than a quar-

ter of their axis 1 funds to agricultural value added

growth which, from 10 years hindsight, was a mis-

take. The reason probably lies in the low effective-

ness of these payments — value added does not

necessarily mean enhanced competitiveness if the

product structure is mis-selected.

Figure 3. Share of farms by UAA in the NMS in 2010 (%)

Source: Own composition based on Eurostat (2015) data

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Less than 5 ha 5-29.99 ha 30-99.99 ha 100 ha or more

-2,00

0,00

2,00

4,00

6,00

8,00

Bulgaria

Czech Republic

Estonia

Hungary

Latvia

Lithuania

Poland

Romania

Slovakia

Slovenia

1999-2003

2004-2008

2009-2013

Figure 4. Annual GDP growth in the NMS, 1999-2013 (%)

Source: Own composition based on World Bank (2015) data

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

Generation change

Adding value to agricultural and forestry products

Modernisation of agricultural holdings

Figure 5. Distribution of the most important first axis payments

in the programming period 2007-2013 by NMS (percentage)

Source: Own composition based on RDR (2013)

Электронная Научная СельскоХозяйственная Библиотека