МЕЖДУНАРОДНЫЙ СЕЛЬСКОХОЗЯЙСТВЕННЫЙ ЖУРНАЛ № 6 / 2016

5

ÌÑÕÆ — 60 ëåò!

ГЛАВНАЯ ТЕМА НОМЕРА

in the region but also horizontal IIT. He found that

differences in country size and income were posi-

tively related to IIT as is FDI, while distance and IIT

showed a negative relationship. Bojnec and Fertő

(2015) analysed the price and quality competitive-

ness as well as comparative advantage in EU coun-

tries agri-food trade and found that new and old

member states have become more similar in suc-

cessful agri-food competitiveness and comparative

advantages.

Policy-oriented analysis of the lessons of acces-

sion can be found in Möllers et al. (2011) who inves-

tigated the changes in agricultural structures and

rural livelihoods in the NMS and reached several

agricultural policy conclusions, especially regard-

ing the ongoing debate of the Common Agricultur-

al Policy. Gorton et al. (2009) analysed why the CAP

does not fully fit the region and identified several

reasons valid for the NMS. Csáki and Jámbor (2013)

analysed the impacts of EU accession on NMS agri-

culture and concluded that EU accession has had

an overall positive impact, although member states

capitalised their possibilities in a different man-

ner. Kiss (2011) echoed the above conclusion and

added that accession has created an incentive to

NMS agriculture but also had negative effects due

to tough competition in the enlarged market. So-

mai and Hegedüs (2015) investigated the speed of

changes in NMS agri-food sector after accession

and concluded that Poland and the Baltic countries

showed the best performances regarding overall

development. Szabo and Grznár (2015) analysed

the Slovakian position in EU agriculture and ranked

it in the last in their sample due to low input of fixed

assets, intermediate product, livestock units, but

also a lower volume of the provided subsidies than

the advanced countries.

3. Methodology

In line with the aim of the chapter, an innova-

tive tool (the agricultural performance index) is

used to analyse the post-accession agricultural per-

formance of the NMS. The agricultural performance

index is similar to those generally applied by inter-

national organisations to measure and compare

economic performance of a group of countries

(e.g. Global Competitiveness Index, Environmen-

tal Performance Index, etc.). Just like in the associ-

ated reports, past performance is ranked through

different indicators and then aggregated into one.

A similar approach is applied here as 15 different

agriculture-related indicators is captured and then

aggregated to get the agricultural performance in-

dex. Except for Csaki (2004) who used a similar logic

to assess the status of transition, this approach has

not been used to the agri-food sector so far.

The paper analyses agricultural performance of

NMS in 1999-2013. This period is subdivided into

three equal periods (1999-2003, 2004-2008, 2009-

2013) to better assess the impacts of EU accession.

An average for all sub-periods is calculated for each

of the 15 indicators and then averages of the first

and last periods are compared. In order to manage

negative results (i.e. negative changes in specific in-

dicators in time), the value of the smallest average,

pertaining to a country, is added to all countries’

respective changes (changes from 1999-2003 to

2009-2013) and then final scores by country are giv-

en in percentage of the highest value. This method

enables us to give 100 points to the best perform-

ing country (i.e. the country with the highest posi-

tive change for an indicator) and continuously less

to those performing worse. As countries are ranked

on the basis of their own performance, initial differ-

ences among countries do not play a role. The list

of the 15 indicators selected is given in Appendix 1.

As a major source, the paper uses the Eurostat

database but FAO andWorld Bank datasets are also

used in some cases. Note that Cyprus and Malta are

excluded from the analysis because of the marginal

importance of the agricultural sector in their econ-

omies compared to other NMS. Croatia is also ex-

cluded on the basis that her 2013 accession does

not allow any impact analysis considering the time-

frame of the sample. We are also aware that the

2007 accession of Bulgaria and Romania slightly

changes the interpretation of our results, though

we still think that the performance of these coun-

tries are comparable to other NMS based on histori-

cal and geographical reasons.

4. Agricultural performance indices

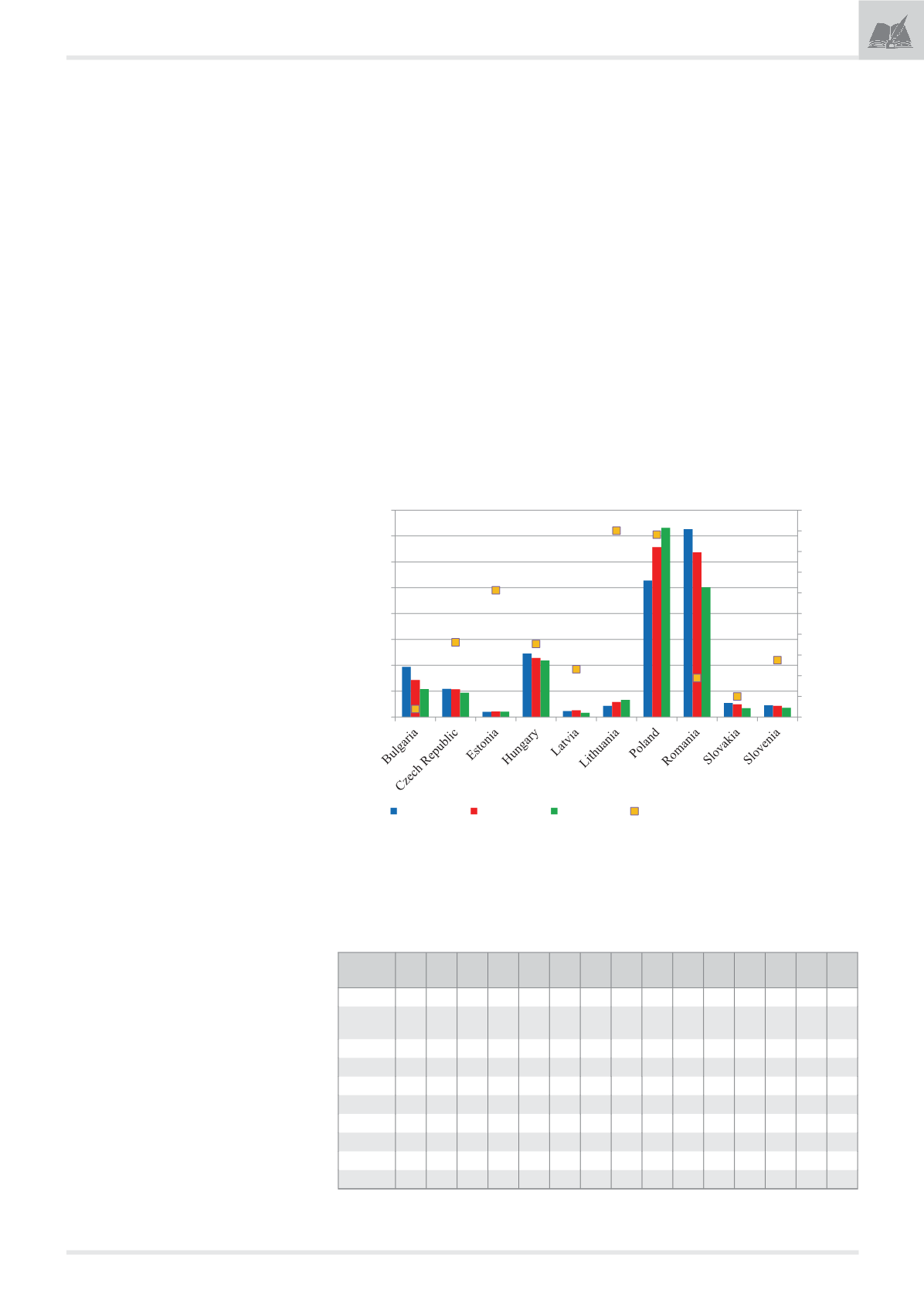

The first indicator describing the performance

of agriculture is gross value added at real prices.

There are very significant differences in this regard

among NMS (

Figure 1

). On the one hand, Slovenia

had a gross value added of 759 euro per hectare

on average in 2009-2013, while Latvia could only

reach 90 euro per hectare at the same time. What is

more important, only Estonia, Lithuania and Poland

could increase gross value added in agriculture af-

ter accession, while huge falls are observable in the

others (including Bulgaria’s sharply decreasing per-

formance of 44% from the first to the last period

analysed).

It is evident from

Figure 1

that Lithuania be-

came the first in agricultural gross value added

performance (showed the highest increase from

1999-2003 to 2009-2013), thereby received a score

of 100. On the other end, Bulgaria showed the big-

gest fall here and got zero points (see first column

of

Table 1

).

Agricultural performance can also be measured

by sector. Indices 2-7 actually capture country per-

formances by their diverging sector outputs. For

instance, Lithuania doubled her cereals output

from 1999-2003 to 2009-2013 (from 262 million to

539 million euro), thereby obtaining 100 points for

the second index (see second column of

Table 1

).

Figure 1. Changes in agricultural gross value added in real terms in the NMS, 1999-2013

(euro/ha and percentage)

Source: Own composition based on Eurostat (2015) data

-50%

-40%

-30%

-20%

-10%

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

0

1000

2000

3000

4000

5000

6000

7000

8000

1999-2003 2004-2008 2009-2013 Change (2009-2013/1999-2003)

Table 1

Summary of agricultural performances in NMS

Country/

Index I1 I2 I3 I4 I5 I6 I7 I8 I9 I10 I11 I12 I13 I14 I15

Bulgaria

0

44 73 6

0 0

28 6

0

7 17 33 53 76 56

Czech

Republic 37 25 26 27 96 31 48 47 38 21 18 28 28 59 29

Estonia 67 77

100

3 73 82 84

100

39

100 100 0 100 100

35

Hungary 37 41 36 38 38 45 23 31 37 17 3 62 19 25 45

Latvia

22 82 73

0

63 67 85 55 9 15 78 12 57 69 38

Lithuania

100 100

69 79 28 78 79 52 89 58 41 53 45 81 33

Poland 98 48 53

100 100 100 100

63

100

46 17 92 30 56 81

Romania 17

0

32 49 59 13

0 0

14 18 35 100 17

0

89

Slovakia 7 25 25 23 44 14 23 35 13 25 32 62

0

27

100

Slovenia 27 7

0

88 64 43 43 5 23

0 0

57 3 52

0

Note: The detailed list of indices can be found in Appendix 1.

Source: Own composition

Электронная Научная СельскоХозяйственная Библиотека